Volume 6, Number 1, Winter-Spring 1997

Patricia Harrison and Gary Johnston

Patricia Harrison is Associate Professor, Department of Environmental Design, University of California, Davis, and Gary Johnston is County Director, UC Cooperative Extension, San Joaquin County, Stockton.

The recent winter floods in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys have again brought attention to the serious housing shortages experienced by farm workers and their families. Many lost their homes, both in grower-operated bunk housing and in rental units in Central Valley communities. In several areas, donated assistance in the form of food, clothing, and household items relieved the immediate hardships that farm workers faced, but replacement housing has been extremely difficult to find. As large numbers of migrant workers and families arrive for the major work season this summer, the shortage of housing opportunities will be even further exacerbated. It is time for the state as a whole to address the need for affordable housing for this important population group and to look for new ways to create clean, affordable, attractive dwellings and housing environments.

Various aggravations of operating farm housing for single men have contributed to the decline in availability of employer-managed dwellings. Neighbors complain about (or sometimes simply fear) workers' behavior, noise, and traffic. Government inspections, regular and deferred maintenance, calls from or regarding tenants during their non-work hours, and liability issues all represent unwanted concerns and costs for growers. Housing facilities that cannot withstand heavy use or are not vandal resistant may be cited for regulatory violations that carry substantial penalties. Even minor violations of the housing code, such as torn window screens, can result in large fines.

Nevertheless, growers and labor contractors have shown renewed interest in housing as an important factor in their ability to attract and retain their best workers. If workers can look forward to returning to an area without the stress and insecurity of having to search for lodgings, they are more likely to show up as a dependable, experienced labor force.

Can communities, growers, and farm workers themselves cooperate to create standards for affordable housing, allocate land for it, and find methods to better weave seasonal as well as year-round workers and their families into the overall community fabric? The recent flood crisis could be a catalyst for joint ventures of growers and communities to develop facilities that meet concerns for housing quality, economic viability, and community safety.

Basic Considerations

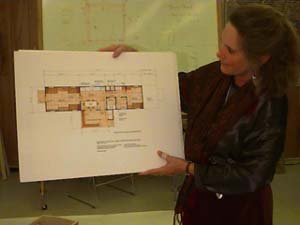

A research and design project to develop plans for a cost-effective, durable, and legal unit to house either six or eight seasonal workers was recently completed at the University of California, Davis, Department of Environmental Design. Sponsored by the UC Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources and the Agricultural Personnel Management Program, the dwelling design offers a realistic approach to housing farm workers either on individual growers' properties or in housing centers that are community-operated or privately owned. Key design principles were that the dwelling had to:

Conformance with all state and federal standards for agricultural worker housing was a primary concern. Within the complex regulatory environment, the basic requirements are in the federal Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act and the California Health and Safety Code, the California Code of Regulations, Title 24 and 25, and the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 29. The California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) has prepared a helpful summary of these rules.

The most fundamental design requirements are that the unit provide each worker 50 square feet of floor area in sleeping quarters and at least one toilet and one shower per ten residents. Additionally, there are requirements for light and ventilation, heat, ceiling heights, space between beds (and bunks), clean water, and heated showers. If workers are permitted to prepare their own meals, a residential quality kitchen may be provided. However, if workers' meals are to be prepared by a cook, then a more costly, commercial kitchen must be supplied, and regular health department inspections are required. Kitchen and dining spaces must be separate from sleeping spaces, and bathrooms must be directly accessible to all residents.

Construction Standards

In general, the regulations demand that the dwelling be well constructed and sanitary, and that normal precautions for safety be maintained. Beyond the basic requirements are building specifications related to format of construction. Depending on whether the dwelling is site-constructed, a mobile home, or a manufactured dwelling, specifications for such features as the number of exits, minimum room sizes, and exit windows on second floors may come into play.

We decided to use a factory-constructed format for the dwelling, both to capitalize on economies of mass production, including relatively low labor costs and standardization of construction materials, and to ensure uniformity of construction method and quality. Manufactured housing is often confused with mobile home and recreational vehicle construction, but there are differences in the regulatory requirements and quality of materials used. The manufactured housing standard selected for the seasonal dwelling unit is that of the Multi-Unit Manufactured Housing label. The choice was based on the consideration that, if purchased by a public agency and rented to seasonal workers, the unit could also be used "off season" for short-term emergency housing for families.

Controversy in farm worker housing often arises over the quality of materials used for long-term maintenance of the housing environment. However, basic regulations for construction of housing are reasonable. Heavy use of bathroom and kitchen facilities necessitates high-quality construction and institutional-quality finish materials. Light-weight window screens, mildew on walls of under-ventilated showers, and deteriorated flooring are common problems in bunk houses.

In cooperation with manufactured-housing industry representatives, we developed an upgraded specification that meets site-built (house) standards: 2x6 exterior walls with R-19 insulation, 2x4 interior walls, R-30 insulation in floors and ceiling, and double-paned vinyl-framed windows. Units built to these standards through cost-effective factory methods promise to be strong, energy efficient, and relatively fast to produce.

The design complements the substantial insulation with provision for cross-ventilation and a building orientation that minimizes both water heating expenses and unwanted heat transfer between interior and exterior. The unit has a central furnace and optional air conditioning. If the windows and shades are closed during the day and then opened during cool evenings, residents will be able to maintain comfortable temperatures with very little use of cooling or heating appliances. The unit plan includes a "low-tech" approach to water pre-heating that will make sufficient warm water ready for peak shower use periods.

Recommended furnishings for the dwelling unit are built by a non-profit company in Oakland, California. The beds and closets are constructed of 3/4-inch-thick, medium-density fiberboard, one of the strongest and most dimensionally stable materials used in furniture. Doors and drawers are fitted with lock hardware with which residents can use their own padlocks. A cleanable, inexpensive, institutional-quality mattress produced for single-resident-occupancy hotels was selected to complete the interior furnishing of the unit.

Portability

The dwelling is a long, narrow building measuring 14 feet wide by 58 feet long for the six-person unit or 14 feet by 68 feet for the eight-person version. It is designed either to be placed on a permanent perimeter foundation or to be set on temporary piers and surrounded with a screening skirt. The unit can be moved without significant structural damage.

This portability offers several benefits. The unit can be temporarily situated in flood plain areas and moved in periods of emergency. It can be brought into a community on a short-term, provisional basis, and then removed if the arrangement proves unsatisfactory. On the other hand, if the dwelling is placed on a permanent foundation, it can function as well as a site-constructed building and can provide years of use and an attractive appearance.

While the dwelling is not designed to be moved frequently, it can be relocated and set on piers or a foundation at moderate cost. A specialized towing truck and road pilot cars are required for the move. One estimate for moving the unit from the factory to a site about 75 miles away and setting it on temporary piers was nearly $1,000.

Designing for Environmental Quality

Within the restrictions of law and manufacturing technology, we obtained and heavily used guidance from many personal interviews in the California agricultural community, especially with workers. While sleeping space, bathroom facilities, and the kitchen were designed at the required minimum areas to keep construction costs as low as possible, the overall environment that they are part of has a residential character and meets residents' needs for privacy, cleanliness, and a home-like setting.

The kitchen is the main "living" area of the dwelling, and its extension to a large outdoor deck provides for comfortable, uncrowded, shared use. There is a television hook-up over the refrigerator for easy viewing by all. On the deck are hook-ups for a washer and dryer. Many of the growers, farm workers, and health professionals interviewed in the project stressed the need for a convenient place to regularly launder clothes.

Many farm workers interviewed stated they would readily pay to live in the unit as designed. They suggested that a rate of $5 per day would be reasonable for a place to sleep, shower, do laundry, and prepare food. Workers suggested that a pay telephone be installed to provide for communication with contractors and growers and timely reporting of any emergencies. They also expressed a need for good exterior lighting on both sides of the unit to help them see their cars and observe potential intruders.

From Concept to Reality

The biggest question at this point in the project is about the price of the unit. Since the dwelling is not yet in production, the accuracy of cost estimates cannot be established. The upgraded handicapped-accessibility specification, low-maintenance finish materials, and vandal-resistant lighting and other fixtures have introduced new vocabulary and costs to the manufactured housing industry.

Currently, a migrant center for 64 men is being planned in Riverside County. It will use eight of the dwelling unit prototypes, and when this project is bid, a clearer picture of production costs will appear. If the dwelling cost approaches $40 per square foot, site construction may become a more attractive alternative in some locations. However, the dwelling designed in this prototype has met all standards in California, and its use will be approved by the state Department of Housing and Community Development for all localities. The advantages of a well-designed "off the shelf" dwelling unit that growers and community groups can purchase with pre-approval from the state may outweigh even a small cost disadvantage.

State legislators are proposing bills that will offer tax credits to both public agencies and private individuals who wish to create new farm worker housing. Perhaps the tremendous suffering experienced by both farm workers and farmers during the winter floods will, ironically, accelerate innovation in approaches to developing farm worker housing, funding arrangements, and collaborations between growers and communities.